Dear advocates of ocean conservation,

You have made it clear—you have grave and wide-ranging concerns about the impacts any future extraction of deep-sea minerals would have on the marine environment. Some of you passionately campaign to stop the exploration of potential deep-sea resources of critical minerals altogether. At the same time, a different set of concerns is being voiced within communities focused on climate change, development and national security – limited access to a secure supply of critical minerals will rule out the energy transition and continued development at the currently planned scale and timeline. Despite appearances, I believe these concerns are reconcilable. Agreeing on what matters most is not impossible. Honest conversations about real-world trade-offs are hard but, again, not impossible. The first step is simple: we all need to show up with an open mind and sincere commitment to engage with the problem and each other. With this letter, I’d like to appeal to a handful of organizations who are willing to take that first step.

We welcome constructive engagement.

Dozens of members of the ocean conservation community are observers and active contributors to the regulatory process at the International Seabed Authority (ISA). You have helped set aside 43% of the Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ) – the primary focus for exploring polymetallic nodules – into areas of particular environmental interest, which are now protected from exploration and exploitation. Your comments have led to stronger protection for the marine environment in the ISA’s draft rules, regulations and procedures ensuring that the future polymetallic nodule industry will only be allowed to proceed under protective and precautionary rules. But on the industry side, the relationship has become antagonistic. I would like to help change that. After a decade of exploration, we have data on real-world impacts to share and important decisions to make. We would welcome constructive engagement.

We have a shared destination.

As a company, our destination is a carefully managed metals commons that is used, recovered, and reused for generations to come. No more metal lost to landfills, nature largely left alone and most of our needs met through recycling – with the same metal stocks serving humankind through countless cycles of technological ingenuity. You call it a circular economy. We call it metal metabolism. It is the mission of The Metals Company to find a workable path to that future.[i] Driving global metal recycling rates up now is important because it creates a tailwind that over time will get us to our destination faster. What it doesn’t solve is the much bigger problem: as long as the world’s metal demand keeps growing, existing metal stocks will not be enough.

The world needs 500 new mines.

The alarm bells from industry analysts have been getting louder by the year: unprecedented quantities of critical minerals will need to be mined in the coming decades. For critical metals like lithium, nickel, cobalt and copper, around 500 new mines need to be brought online in the next 5-10 years to meet the necessary speed and scale of the energy transition alone.[ii] This means we will need to mine more of these metals in the next 30 years than we have mined in all of human history.[iii] Given that it takes between 5 and 25 years to develop a new mine, some have argued that the critical minerals bottleneck has already rendered Net Zero by 2050 impossible.[iv]

Turning terrestrial reserves into responsible mines is a challenge.

Ocean conservation organizations sometimes argue that deep-sea mining is not needed because land-based reserves of critical minerals are enough to meet global demand, and that mining on land can be done responsibly. If you look at land-based reserves of the most critical minerals, indeed, there is plenty of ore in the ground.[v] However, reserve numbers say nothing about the likelihood of reserves turning into new mines. The numbers don’t show the declining quality[vi] or increasing capital intensity[vii] of any given development project. They don’t say much about the ecosystems and their biodiversity, local communities and indigenous people that would be impacted by mining, how much water and energy mining and downstream processing will use, how much waste, CO2 and other emissions metal production will generate, how difficult or costly these impacts would be to manage. They also don’t say much about the opposition any new development project will encounter, how many years a mining permit will take to secure and how often they get denied because local communities do not want mines near where they live.[viii]

Polymetallic nodules offer intrinsic advantages.

As a company, we did not choose to focus on polymetallic nodules because we thought it would be an easy resource to develop. We chose to focus on polymetallic nodules because we saw many fundamental advantages compared to land-based ores that made it worth pursuing: the polymetallic nature of the resource means that a single nodule project can produce four metals—nickel, copper, cobalt and manganese—that would require three separate new mines on land. Far offshore sites mean that operations are not taking place in someone’s backyard. The depth of the sites means we would disturb less life (both in terms of biomass and species richness) compared to ecosystems hosting land-based reserves of the same minerals.[ix] The far and wide stretching nodule fields lend themselves to conservation strategies. Once aboard the transport vessel, we could readily take nodules for processing to sites with low carbon electricity—a commitment we made as a company several years ago. The absence of toxic levels of deleterious elements means we could turn all of nodule mass into products and generate no solid waste—a goal we accomplished with our processing flowsheet design and pilots.

Can we do better than the alternatives?

As a company, we see it as our responsibility to track the full stack of our impacts, make sure our net impacts on people and planet are positive, and change course if we get off-track. Crucially, our baseline for assessing net impacts is not ‘develop the nodule resource’ or ‘do nothing’. New mines will be established; nickel, copper, cobalt, and manganese units will be produced and there will be damage in the process. Our baseline is the expected impacts of the actual pipeline of development projects aiming to produce the same metals—whether it’s nickel laterite projects from underneath the tropical rainforests in Indonesia, nickel sulphide projects from underneath boreal forests in Canada or cobalt sulphides from the Miombo woodlands in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Can we do better than the other real prospects of meeting growing demand in our chosen metals? Over the years, we have supported several lifecycle impact assessments (LCA) looking at how conventional production routes compare to polymetallic nodule projects. Most recently, we have commissioned an independent commercial LCA—where an updated nodule project model was built and results compared to impacts of specific land-based production routes for the same metals.[x] This gave us a more granular picture, and results were encouraging—the probability that our nodule projects would do better than most (but not all) land-based development projects on carbon, waste, water and toxicity is high. However, this latest LCA did not cover the impact area that the ocean conservation community cares most about—impacts on marine biodiversity and ecosystem function. This is the impact area where we have and will continue to invest most of our capital and effort.

Our understanding of marine ecosystems is progressing rapidly.

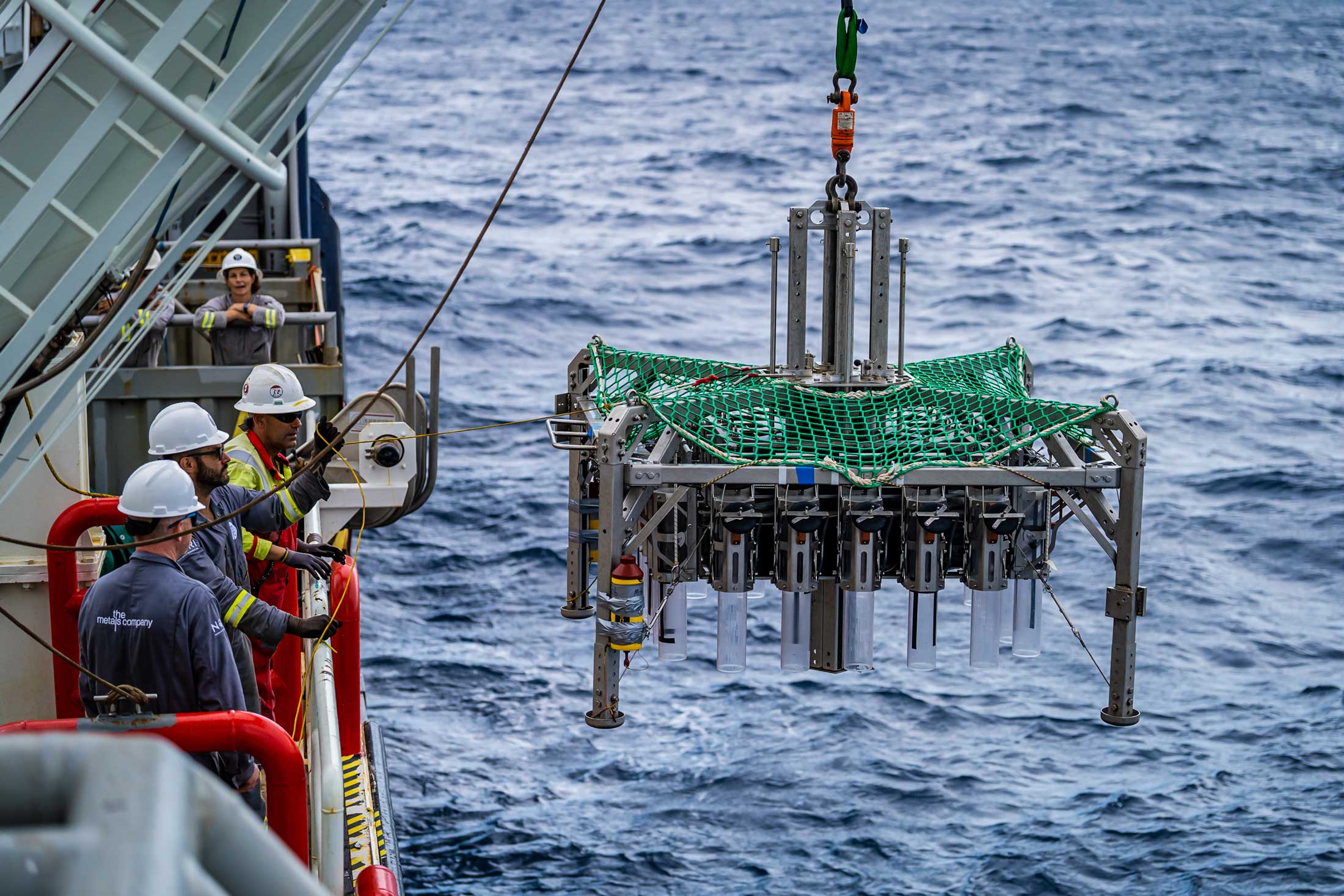

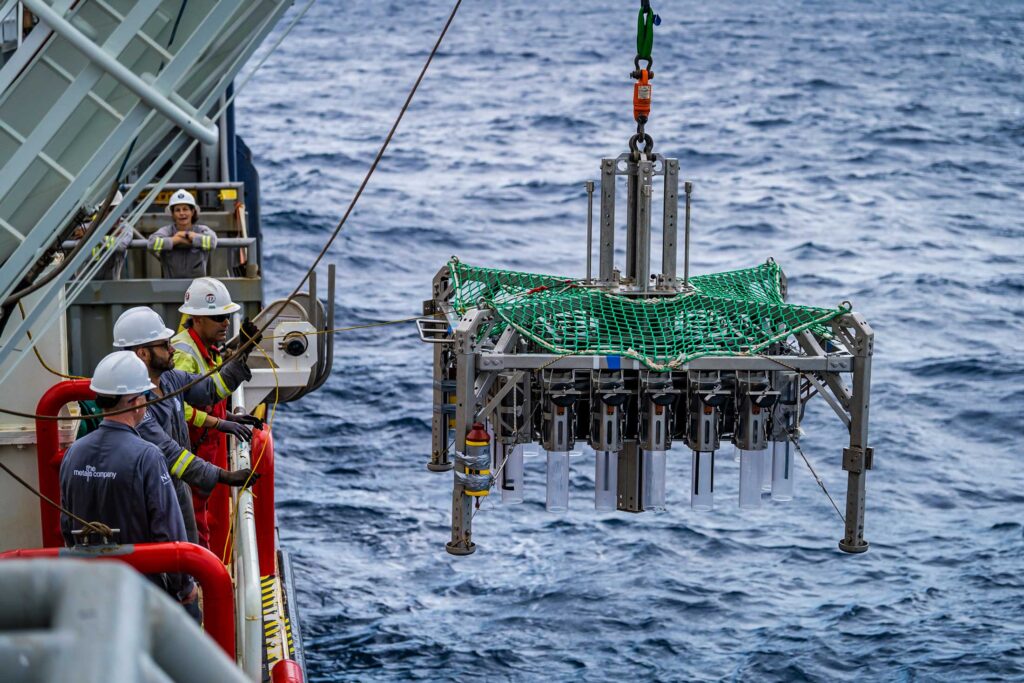

Many of you believe that current knowledge is insufficient for effective management of the marine environment.[xi] This assessment predates the dataset collected by our subsidiary NORI that we recently started to share with the global community. Since 2012, we have mobilised and conducted 18 offshore campaigns to develop a rigorous environmental baseline and impact assessment in collaboration with world-leading scientists and marine industry specialists, encompassing 478 days onsite in the CCZ. We now have one of the world’s most extensive, integrated deep-sea datasets that extends from the seafloor to the surface. In July 2023, the ISA submitted the first batch of the NORI dataset to UNESCO’s Ocean Biodiversity Information System (OBIS), the world’s largest database on marine biodiversity, increasing the biodiversity occurrence records for the CCZ by about 150%.[xii] This submission represents less than half of the total data collected by NORI on the NORI-D area—all of it will be submitted to the ISA in Q3 2024 and then OBIS for public access. We have worked with 18 leading marine research institutions and expert industry contractors to collect and make sense of this data, and all researchers involved are free to publish their findings in peer-reviewed literature. Eight papers have already been published and we expect dozens if not hundreds more to follow in the coming months and years. The data collected will inform the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for proposed nodule collection operations on NORI-D and the ecosystem-based Environmental Management and Monitoring Plan (EMMP) will monitor indicators of environmental change to ensure operations are conducted within safe limits. We will continue to build our knowledge of the CCZ and contribute to the world’s understanding of the deep-sea environment.

Transparency is how we hope to earn your trust.

All this work forms the scientific foundation of our Adaptive Management System (AMS) which will draw upon years of research and expertise from leading marine institutions and hundreds of environmental sensors deployed throughout the entire water column in our NORI-D project area. We now believe we have sufficient data to assess and manage the environmental risks of a small-scale operation while we collect more data as part of the EMMP. We intend to start small and proceed with caution and care. Most people assume that far offshore, deep-water operations will be “out of sight, out of mind” and, therefore, difficult for the regulator to inspect and control. The AMS is intended to be the eyes and ears of our operations not just for us and our offshore partners but for the regulator and key stakeholders, enabling near real-time environmental and operational management of our activities. Together, we hope to set the bar for the industry going forward. Far offshore and at-depth operations under the oversight of an international regulator could become the easiest resource extraction projects to monitor.

To highlight our commitment to being a transparent organisation, we have just this week published our 2022 Impact Report and Sustainability Approach. Our Impact Report provides a view of the anticipated impacts of our operations and our efforts to reduce them, while our Sustainability Approach sets out our vision, plan and sustainability goals.

We expect a Mining Code that protects the seabed for the shared benefit of humankind.

There is little doubt in my mind that nodule collection operations will only be permitted and take place under a regulatory regime we can all be proud of. Protection of the marine environment is not a nice-to-have, it’s mandated under UNCLOS. A precautionary approach and stakeholder inputs are embedded in the workings of the ISA and many members of your community are active contributors to the process. I know you will not settle for anything less than the strongest protections for the marine environment. As a company, we look forward to the final Mining Code and operating within the globally agreed guardrails. We also look forward to paying our fair share of royalties to the ISA and our sponsoring state Nauru—thereby doing our part in ensuring the benefits of developing seabed resources are shared with developing nations.

I am looking for the few who are willing.

For the last few years, we have had lively exchanges at forums, in the media and during protests on land and at sea. I recognise that not everyone supports our plans, and that our critics have valid questions, concerns and challenges. With this letter, I invite the willing few to sit down with us. All I ask of you is an open mind, sincere desire to solve real-world problems and readiness to dive deep. Our environmental team would be pleased to go into the specifics and nuances of our first nodule project: go through the data, share what we have learned, issues we are still working on and mitigation options we have at our disposal. We want a constructive engagement where both sides are heard. It’s a heavy lift and it will take time. But what worthwhile endeavour is ever easy and quick?

Respectfully,

Gerard Barron

CEO, The Metals Company

[i]https://metals.metrio.net/indicators/why_we_exist/circular_metal_economy_future

[ii] IEA, IEA Summit on Critical Minerals and Clean Energy, September 28, 2023. Comments from 4m00s-4m40s; The World Bank, “Minerals for Climate Action: The Mineral Intensity of the Clean Energy Transition”, April 2020.

[iii] IEA, “The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions,” May 2021

[iv] Wood Mackenzie, “Faster decarbonisation: back to basics for the mining industry?” November 2, 2021.

[v] U.S. Geological Survey, “2023 Commodity Summary – Nickel”; U.S. Geological Survey, “2023 Commodity Summary – Copper”; U.S. Geological Survey, “2023 Commodity Summary – Cobalt”; U.S. Geological Survey, “2023 Commodity Summary – Manganese.”

[vi] Calvo et al.,“Decreasing Ore Grades in Global Metallic Mining: Atheoretical Issue or a Global Reality?” November 7,2017.

[vii] BN Americas, “Lower production, higher cash costs for Chile’s copper miners,” June 11, 2022; BNN Bloomberg, “Giant miners to see record profits slip as cost pressures bite,” February 12, 2022.

[viii] Henry Fountain, “Alaska’s Controversial Pebble Mine Fails to Win Critical Permit, Likely Killing It,” Nov. 25, 2020; Ernest Scheyder, “Rio Tinto’s 26-year Struggle to Develop a Massive Arizona Copper Mine,” April 19, 2021; U.S. Department of Interior, “Interior Department Takes Action on Mineral Leases Improperly Renewed in the Watershed of the Boundary Waters Wilderness,” Jan. 26, 2022. Ivana Sekularac, “Serbian PM Sees No Chance for Reviving Rio Tinto Lithium Project,” December 13, 2022.

[ix] Bar-On, Yinon M et al. “The biomass distribution on Earth.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America vol. 115,25 (2018): 6506-6511. doi:10.1073/pnas.1711842115; Wei C-L et al. “Global Patterns and Predictions of Seafloor Biomass Using Random Forests.” PLoS ONE 5(12): e15323. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015323.

[x] Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, ”Life Cycle Assessment for TMC’s NORI-D polymetallic nodule project and comparison to key land-based routes for producting nickel, cobalt and copper,” March 2023; Summary report of Benchmark LCA, March 2023.

[xi] Amon et al. “Assessment of scientific gaps related to the effective environmental management of deep-seabed mining,” Marine Policy, 138, April 2022; Multiple authors; Marine Expert Statement Calling for a Pause to Deep-Sea Mining,

[xii] The Metals Company. “Biodiversity Data from NORI-D Exploration Area Now Available on UNESCO’s Ocean Biodiversity Information System, Increases Biodiversity Records for the Clarion-Clipperton Zone by About 150%.” 2023.